Alexandra Grey proudly holding the physical product of her PhD research

My university will shortly require only a digital copy of each PhD after it has been examined and awarded, but luckily I snuck into the tail-end of the hard copy era. I say ‘lucky’ because my hard copy of my own hard work is a lovely, and hefty, thing to hold. And I’m not the only one who wants to hold it; having a physical final product has been meaningful to friends and family who buoyed me through the last four years.

When I collected the hard-bound copies I thought, ‘my work is complete’. Complete enough to celebrate, at any rate! My Language on the Move colleagues have warmly marked the milestone. But while the PhD is over the research doesn’t feel finished. I am still drawn to the subject of my thesis – how China’s minority languages policies operate today – because of (rather than despite) my years researching it. For the thesis, I chose a quote from Heller as my opening epigraph:

The globalised new economy is bound up with transformations of language and identity in many different ways … Ethnolinguistic minorities provide a particularly revealing window into these processes. (Heller, 2003, p. 473)

These different transformations are ongoing; this window remains. So, I remain curious about sociolinguistics in the Sinosphere (and much else in the Sinosphere besides). Every time I write up a paper from the thesis I think up further questions to investigate. I’m working out how to share the findings with my generous participants and collaborators. And I’m preparing to return to China later in 2017 for a different project (on English and the globalisation of university education).

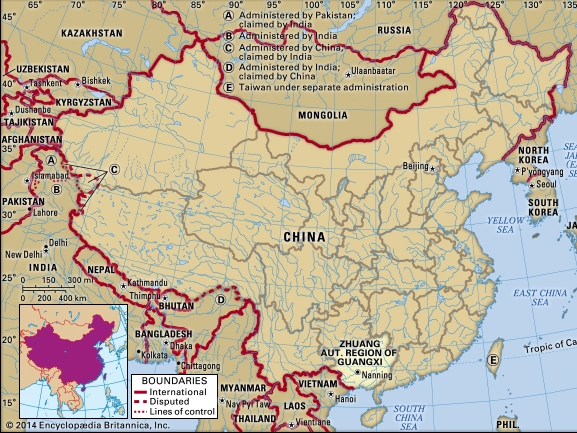

The thesis is not only relevant to linguists but also to Sinologists and political scientists. It’s an ethnography of language policy; that is, it’s about the lived experiences of state practices regarding a minority language. Rather than merely analysing what the minority language polices say, or what language practices everyday people have, it combines these angles. This makes for a lot of ground to cover, so I took a case study of just one language, Zhuang, the language of China’s largest official minority group, a group who have autonomous sub-national government over the Guangxi Zhuangzu Autonomous Region. The thesis investigates what language ideologies are produced and reproduced in official language rights discourses and policies, and how social actors receive, resist or reproduce these.

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica)

The research takes an ethnographic approach and draws on interviews with over sixty participants, texts collected from public linguistic landscapes, fieldwork observations and a corpus of Chinese laws, policies and official policy commentaries.

The analysis commences with a critical examination of the procedures of Zhuang language governance, finding that the language policy framework neither empowers Zhuang speakers nor the institutions tasked with governing Zhuang because authority for language governance is fractured and responsiveness to changing conditions is limited. Furthermore, the Zhuang language governance framework entrenches the normative position of a ‘developmentalist’ ideology under which Zhuang is constructed as of low value. Next, the analysis follows Zhuang language policy along its trajectory into practice. The thesis examines how language policy is implemented at different levels of government, and how Zhuang language governance is understood and experienced by social actors, concentrating on two key mechanisms of language policy: first, the regulation of language displayed in public space; and, second, the regulation of language in education.

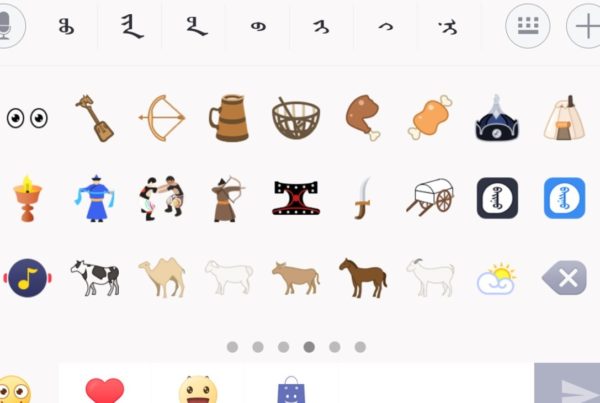

With regard to public space, the thesis examines a municipal legislative intervention under which Zhuang has been added to public signage. It finds that Zhuang language is rarely displayed outside areas under Zhuang autonomous regional government, and that even within these areas Zhuang is almost exclusively displayed on government signage. The thesis then extends the linguistic landscape approach, analysing the various ‘readings’ of Zhuang landscape texts by viewers, including some who negatively evaluate the signage as tokenistic and many who simply do not ‘see’ the displays of Zhuang. This is one of the more surprising findings: it’s so easy to assume (as a policy-maker, an academic or a passer-by) that a bilingual street sign will be read and used by bilingual viewers who speak that language, that it will be seen as bilingual, that it will be seen at all. As my research discovered, these are not well founded assumptions.

Bilingual and triscriptual street sign in Nanning, GZAR

Finally, the thesis examines education policy under which Zhuang is introduced as a study subject at a limited number of universities after its near-total exclusion from primary and particularly secondary schooling. It finds that students who – against social norms and values – choose to study Zhuang at university nevertheless largely adopt the language ideologies of the pre-tertiary schooling system, namely the belief that Zhuang is not an educated person’s language and not useful for socio-economic mobility.

Overall, the study finds that Zhuang language rights and policies, despite being powerful official discourses, do not challenge the ascendant marketised and mobility-focused language ideologies which ascribe low value to Zhuang. Moreover, although language rights and policies create an ethno-linguistically divided and hierarchic social order seemingly against the interests of Zhuang speakers, Zhuang speakers may nevertheless value the Zhuang identity discursively created and invested with authority by this framework.

I’m now looking forward to reworking my doctoral research for publication, touching base with Zhuang participants, and getting started on my post-doctoral journey.

Alexandra Grey’s PhD thesis, “How do language rights affect minority languages in China? An ethnographic investigation of the Zhuang minority language under conditions of rapid social change” (Macquarie University, 2017) can be accessed through our PhD Hall of Fame.

Reference

Heller, M. (2003). Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(4), 473-492.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Here is the Macquarie University’s copy http://www.researchonline.mq.edu.au/vital/access/manager/Repository/mq:70226?queryType=vitalDismax&query=Grey%2C+Alexandra&f0=sm_creator%3A%22Grey%2C+Alexandra%22

For transparency, I note that the copy of my thesis available here in the PhD Hall of Fame has received minor corrections which make it different from the official, post-examination version kept by Macquarie University. Specifically, in this one I have corrected a few typos and layout problems and made corrections to the discussion of the trilingual museum sign in Section 5.2.4.1 Linguistic References to “Zhuang Language”.

Thank you, Dr. Grey! I am from the capital city of Guangxi Zhuangzu Autonomous Region and I would like to share some personal experience about this topic.

As a local dweller, I also asked the same question to my mon (who is the descendant of a local Zhuang in Heci county): why I seldom see people speak Zhuang even I am in a Zhuang autonomous Region? And my mon replied: Visit the autonomous counties, you will have an opposite conclusion. In the following years we visited some counties, town around Jin Cheng Jiang city and the local people proved my mon’s words. In years I sometimes thinks of the reason for the sharp contrast in my hometown. Later I will take a time to look your PhD thesis and I hope I can find answers in it.

Hi VinN. Interesting to hear your experiences, which echo those which some people reported to me during fieldwork. I am not making the claim that no-one speaks Zhuang, but it is very noticable that Zhuang is not spoken much in bigger cities, while it is still spoken more commonly in more rural areas, areas that the literature describes as “peripheries”. My thesis argues that this has a lot to do with both the place of language in urban environments and the economic, educational and mobility “capital” of Zhuang. (“Capital” here is the term proposed by Bourdieu).

Alex, you’re shining!! Best wishes, Sadami

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/f6bc1cac5e49afa0c91ae1fca873d6017d71ff9c2cbdf8aa5ba98e3fd22e074b.jpg

Great thesis, congrats, Alex! Go!! Leap into your bright future! I hope more and more students will follow Alex and this group. Best wishes, Sadami https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/e7965abde204b2d12f007977b32d11763a92e3ffcc8a419f0b49de6f9bcc9183.jpg

Stunning image!