Manus Island Detention Centre, where Faysal Ishak Ahmed collapsed (Source: ABC News)

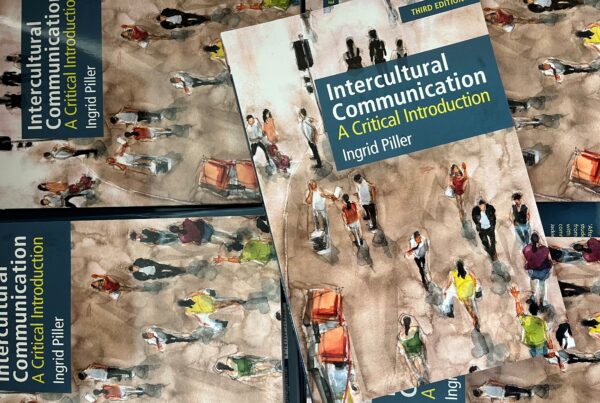

On December 23, 2016, as most Australians were winding down for the holiday week ahead, Faysal Ishak Ahmed, a 27-year-old man from South Sudan died in immigration detention when he collapsed with a seizure. After his death, it emerged that the young man had repeatedly presented at the facility’s healthcare provider over a period of several months for a range of health issues such as stomach upsets, high blood pressure, fevers and heart problems. However, he never got to see a doctor and each time was dismissed by the nurse on duty. He described one such incident to his friends shortly before his death:

I went to the [healthcare provider] and then [they] told me that, hey you don’t have anything, you are not sick and you’re pretending to be sick, and from now on, we don’t want you to come down here, so please stop coming here. (Quoted from ABC News)

Even if rarely with fatal consequences as in Ahmed’s case, the experience of not being listened to and not being taken seriously is one that many people who speak English “with an accent” can relate to.

Cases such as these where patients with limited proficiency in the dominant language are not taken seriously and oftentimes simply ignored are not unique to Australia, as a US study of doctors and nurses working with patients with limited English proficiency demonstrates (Kenison et al., 2016). In a quote that has almost uncanny echoes of Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s experience on the other side of the world, one junior doctor reported this conversation with a senior clinician to the researchers:

And he said, ‘Oh, you know we see this, a lot of this Haitian chest pain.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean by that?’ And he said, ‘Well, they come in and the tests are negative, and they have a different perception of pain than other people.’ He kind of wrote it off that way. I felt a little weird that it was written off that quickly. To write off the chest pain on a patient who is having trouble communicating because she’s using a phone interpreter. (Kenison et al., 2016, p. 3)

Faysal Ishak Ahmed, who died after being dismissed by health care provider (Source: ABC News)

Most people assume that language proficiency is a specific skill set that a person has or does not have. It is further assumed that, once migrants have reached a particular level of English, they will be able to “integrate” and interact on a level playing field. This view of language proficiency as a property of the speaker is fundamentally mistaken because we don’t use language as isolated individuals. Language is a social tool and language proficiency is jointly constructed in interaction. To be able to form grammatically correct sentences does not necessarily translate into “the power to impose reception”, as sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has pointed out.

A wealth of sociolinguistic evidence demonstrates that non-standard speech, such as the English of multilinguals that shows traces of their non-English-speaking background (NESB), is rarely taken just as a specific way of speaking but as an index of a particular identity – often the identity of someone who is considered less worthy. Ahmed was assumed to be a fake patient. In our research with adult NESB migrants here at Macquarie University, we have met highly qualified job applicants whose skills were obscured by their accents; capable and diligent students who were considered lazy and poorly motivated on the basis of their English expression; or consumers who did not manage to return faulty products within the warranty period because shop assistants pretended not to understand them.

Mundane interactions such as these have broad social consequences. Far from interacting on a level playing field, NESB speakers have unequal opportunities to access employment, education, health care or community participation.

While we have become increasingly vigilant with regard to discrimination based on race, gender, sexuality or disability, linguistic disadvantage is far more difficult to recognize. Partly this is due to the fact that Australians who speak English as their first language have fewer and fewer opportunities to learn another language and hence are poorly equipped to relate to the challenges of language learning. As a result, discussions of linguistic diversity are often based on the false premise that individuals exert full control over their linguistic repertoires. In reality, learning a new language while also trying to do things through the medium of that language – to work, to study, to present your symptoms to a nurse – is a double challenge and these two aims of communication are not always compatible.

To mitigate linguistic disadvantage requires both individual and institutional efforts. Individuals need to be prepared to share the communicative burden rather than placing it exclusively on the shoulders of NESB speakers. Institutions need to put in place adequate policies and training opportunities to identify and meet language needs. Switching on to an unfamiliar accent may require extra mental effort and catering to the language development needs of everyone in an institution requires extra resources. However, these investments will pay dividends by contributing to the kind of inclusive and cohesive society we all want to live in.

How language barriers such as these can be bridged will be the focus of tomorrow’s “Bridging Language Barriers” Symposium. We’ll be looking forward to welcoming attendees to Macquarie University but if you cannot attend in person, you can still join the conversation with our team of live-tweeters. Our Twitter hashtag will be #LOTM2017. Follow @Lg_on_the_Move

![]() Kenison TC, Madu A, Krupat E, Ticona L, Vargas IM, & Green AR (2017). Through the Veil of Language: Exploring the Hidden Curriculum for the Care of Patients With Limited English Proficiency. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 92 (1), 92-100 PMID: 27166864

Kenison TC, Madu A, Krupat E, Ticona L, Vargas IM, & Green AR (2017). Through the Veil of Language: Exploring the Hidden Curriculum for the Care of Patients With Limited English Proficiency. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 92 (1), 92-100 PMID: 27166864

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

I think in Ahmed’s case he was not taken seriously because he was unable to provide the urgency in his pain / sickness. Our words do not directly transfer exactly, meaning that a word in Spanish such as the ‘severity’ of the pain may not equate in the English language. If we look at food for example, a ‘hot’ spice in food (i.e. very spicy to our mouths) in Australia may equate to a ‘mild’ spice (i.e. not so spicy to our mouths) in Spain. Much like language our ‘performance’ of what we are transmitting is different to how we ‘perceive’ the outcome. I have felt the same when I travel to South America. I have eaten different variations of food and ‘ice’ has been added to my drink. My stomach is uneasy and it is very difficult to describe such pain to the pharmacist. To them it is indigestion but to me it is far worse than indigestion, due to the variation of food spice or possibly the not so clean water we may be used to in our country. Much like language, we prescribe what we know based on our perception of our surroundings or the environment we are in and then use that performance that one size fits all.

Being educated or maybe those who have experienced different cultures / travelled or have experienced themselves in other countries may have an affect in how we treat others or perceive others from countries who have English as a second language. I had seen one example yesterday when an Irish person was trying to order something and the attendant was very happy to help to convert the menu for him. Possibly he has an understanding of what it is like to be in a different place. The attendants ‘perception’ is associated with wanting to help that person (i.e. performance) as he knows what it is like to be in a foreign land.

Reading this article reminded me of something one of my students shared with me recently. While I’m fortunate not to have experienced this type of discrimination personally, my student in Canada is dealing with it now. In our online class yesterday, she talked about her frustration with being unemployed, and how her friend, who is in the same situation,was hired for a job that she had applied for three weeks ago. The strange part? The HR told her they weren’t hiring, but then hired her friend, who has fewer qualifications. The difference? Her friend speaks English fluently because she was born and raised in Canada, while my student has a thicker Chinese accent.

It’s really unfair how much weight accents carry in situations like this. My student is a better fit for the role, yet she was dismissed because of how she speaks. This article resonated deeply with her experience and highlights how unjust these biases are.

Its really heart breaking to know a young man died just because of his poor English proficiency and societal judgements. Here in Australia What I have found is there is tension mostly because of accent and meaning generation leading to intercultural miscommunication. In my case though being a fluent in English, I have encountered some challenges in my workplace because of the accent I use back from my home country when I firstly arrived on Australia. Generally what I have found i L2 Accents and pronunciations is different from L1 or native speakers which creates problem is language interpretation leading to miscommunication.

Reading the article made me think a lot about my experience as an international student in a linguistically diverse society. I’ve encountered situations where, despite my best efforts to communicate, people seem to dismiss me because of my accent or hesitate when I’m trying to express myself in English. It’s frustrating, especially when I know I’m capable but still feel judged by my language skills rather than my ideas. The article really hit home by showing how these moments of exclusion aren’t just personal struggles but reflect larger societal issues.

For me, this has impacted interactions in both academic and social settings. I’ve sometimes held back from speaking up, fearing my accent would be misunderstood that I might not be taken seriously or people seem to assume my English isn’t good enough to communicate clearly. This experience reminds me of how important it is for people to show more patience and understanding when interacting with non-native speakers like me. Language should be a tool for connection, not a barrier that creates distance.

Oh and I forgot to say, after i learned some Chinese the people never didscriminate me or said I was wrong, but congratulate me for my good accent, or at least they said so… Maybe I have been lucky enough! To add, many Chinese people in China who speakl English are quite open to changes and have knowledge enough to have deep conversations despite any type of accent, especially university students.

This is a good example of how we use to assume things based on our own language perception, but who says who is right and who is wrong? Everyone, for sure, have different perceptions according to own experiences and backgrounds. I’ve experienced few misunderstandings while living in China, as mentioned in past comments, but mostly due to the big culture differences and how they have their own sign language. At the beginning, I used to think they laughed at me because I couldn’t speak Chinese, but later I realized they laughed because they could not speak English, quite opposite, isn’t it? Maybe my western culture led me to assume so at the beginning. My whole experience with Asian people and friends has been nice, most of them too nice that I could not believe they were helping me or giving me lot of things without expecting anything in exchange, which made me feel so appreciated and very welcome to their circle. Having said that, I believe before assuming anything that may cause some discomfort or side effects, we inquire a little bit about the other’s person culture if possible to embrace new knowledge and avoid misunderstandings. Sometimes we just don’t mean it!

Thanks for reading.

When I was younger, I worked hard to eliminate my Korean accent, believing it made me sound less competent in English. I thought mastering a native-sounding accent would earn me more respect, so I focused on that rather than truly learning the language’s deeper nuances. This personal experience mirrors the broader issues discussed in Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s case, where language and accent affected how seriously he was taken, with tragic consequences. It’s not just about fluency but about perception. Like Ahmed, I faced situations where my accent led others to assume I lacked competence, despite speaking grammatically correct English. This reflects a common tension between performance and perception in language proficiency. Linguistic bias can hinder opportunities in healthcare, employment, and education, showing that the social reception of language is just as crucial as its mastery.

I have a personal experience. When I was a university student, I had the opportunity to work in an educational environment at a famous English centre in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. At that time, I was fortunate to lead a presentation about the centre I was working for and the quality of teaching for foreign customers who were partners of the company. Although I had prepared well and had a deep understanding of the content, I was still worried about my ability to convey information in English. When presenting, I found it challenging to keep the language accurate while maintaining a natural and engaging tone for the audience. However, as the presentation progressed, I gradually found my rhythm and confidence. The clients responded very positively, asked thoughtful questions, and showed great interest in what my centre was doing. They not only appreciated the content but also complimented me on how clearly and confidently I presented it. This experience made me realise that, despite my initial language anxiety, performance and confidence are often more important than linguistic perfection.

Fortunately I have not experienced any negativity or tension with my language learning endeavors, but I recall an interesting discussion I had with a teacher who referred to their adult English learners as ‘my kids’ or ‘like my kids’. Curiously, I asked why they had that perception. It was due to their low language proficiency (CEFR A1) – their utterances and pronunciation of some words made them seem younger than they were, despite many of these students possessing very high intelligence and in professional fields such as medicine, law, and engineering in their own first language. The teacher laughed and mentioned that it is very clear and evident they are adults, although this observation stuck with me and got me thinking about how such perceptions may be also found in other professional and social contexts for English learners, and how it can affect their confidence if told their proficiency in the language is childlike.

I consider myself proficient in English and can easily pick up an Australian accent, so I haven’t had many difficulties using the language in Australia. However, there’s a tension between how I perceive my skills and how native speakers react to small mistakes. For example, today at work, a child asked me for paper for a craft. I said, ‘Let me open the cupboard,’ but mispronounced ‘cupboard’ as /kʌbɔːd/ instead of /ˈkʌbəd/. The child immediately asked why I said it that way. Similarly, I once said ‘please’ twice in a sentence, and a child laughed at me. I felt really disappointed in myself because of these minor slip-ups, especially as I consider myself a proficient English speaker. However, at the end of the day, these experiences act as mirrors, helping me reflect on my English proficiency, reminding me not to be overconfident. Learning is a continuous journey.

Earlier this year, I had spent a few months in a boarding house. All the occupants except one were international students. There was a particular male student who I noticed right away on my first week at the facility that kept his distance from any kind of gathering in the dinning/ kitchen area during the evening meals when most of us would converge for dinner. I noticed that he would either go to the kitchen earlier or much later than everyone else. During my first week, I didn’t hear him at all utter a single word as he would just pass me with a smile and a bow. I finally got to speak with him on my second week when I saw him preparing his dinner at about 2pm and I had gone there to get some fruit for myself. I said Hi and introduced myself and asked him for his name. As soon as he told me his name, he added further “Sorry, me Englis no good” I assured him that it’s okay and that all of us in that boarding house are the same. He then added further, “No you Englis, too high”. I laughed and told him that we are the same. That fruit fetching trip of mine to the kitchen ended up with me joining my Vietnamese friend in cooking my dinner so we could continue with our stories. I got to learn that day that Francis came in earlier or later than everyone else to cook his dinner because he had tried to socialize but no one seemed to be interested in talking with him due to his poor English. Due to this he felt embarrassed to speak with anyone. He also felt that way because most of us were university students while he was an ELISCO student. But after much encouragement, Francis joined everyone else in preparing and sharing dinner. This helped him tremendously with his communication, although at times, I felt that some of our housemates preferred to ignore him. I would always step in whenever I realized that this was the scenario as I was aware of Francis’ struggle. When I left the boarding house in June, Francis had gained confidence in himself in conversing in English whilst cooking and sharing dinner with other household members.

What a good example how a little care and effort can make a big difference!

In elementary school, a new girl joined our school within the last term of the year, and she knew next to no English. Due to the area we lived in being 100% monolingual, a lot of people either did not speak to her or laughed at her, calling her stupid because she was automatically placed in the lowest level classes due to lack of English proficiency. There was no interpreter offered to her in her classes, and for the rest of elementary school and most of high school, I never saw her with any friends. It wasn’t until my senior year of high school that I finally heard her voice, and she had graduated top of her class in English studies for the HSC. According to some of her friends, she had only completed that course instead of English Advanced because she was ‘expected to’ because she had a Vietnamese accent and didn’t speak often.

Thank you Ingrid for sharing this article. Related to that i want to share one of my experience with you. As, I worked in the aged care. Sometimes i take the orders from the residents what they want to eat in the lunch or dinner. There is one resident who was teacher in Australia their own time. One day i asked what they want to eat and there was Ravioli and I didn’t pronounce the correct work and she didn’t understand what I’m saying. She checked the orders list and say me the correct pronunciation of Ravioli and after that, she said to me that my English is not so good and at that time i feel insulted and embarrassed also. As, others residents didn’t say anything the easily understood.

Now when i have a shift in which i have to take the orders, before going into her room I pronounced the orders work so many times and when i think that she again told me anything i just change the word like “ravioli” as a “pasta” . I learned so many words but when i go in front of her i really feel embarrassed. So i didn’t say anything in front of her.

That’s really heart-breaking – one would think that, as an aged-care resident, they’d have enough time to be kind and take an interest …

Fortunately, I haven’t faced any similar challenges since I moved to Australia. A couple of months ago when I first came to Australia, I was at Commonwealth Bank setting up my account when I saw an Asian man struggling to explain an issue with his account. The tellers were doing their best to help, but none of them spoke his language. He couldn’t understand the forms, and there was a communication gap. It was frustrating to watch because it was his own money, but he couldn’t figure out what was going on. They eventually resorted to Google Translate to resolve the problem, but it was clear that both parties were losing patience. I felt really bad for him because something as managing your finances shouldn’t be so difficult.

After reading this post, I reflected on my own behavior. There are many stories about social injustice related to language proficiency, but to my own surprise, I realized that associations related to this so-called language proficiency also have an impact on smaller, subtle things in life (which might be concerning as well). To my own surprise, I realized that I too am subject to prejudices based on this matter and this realization happened in my dating life! Where I unconsciously judged a person of being less intelligent based on their accent and English proficiency. And this coming from a non-native speaker as well! This bias even led to being less interested about this person, although we had interesting conversations. I try to be aware of these things, but this reflection made me realize how subtle these internalized biases are and which impact they can have on different levels

Language can be a big part of the attraction … some years ago, I wrote an article about accent and romance 😉

Piller, I. (2008). ‘I always wanted to marry a cowboy:’ bilingual couples, language and desire. In T. A. Karis & K. D. Killian (Eds.), Intercultural Couples: Exploring Diversity in Intimate Relationships (pp. 53-70). Routledge.

Ahmed’s case is very sad and unfortunate. I also felt that when I talked about symptoms of my body, it didn’t feel as accurate as when I speak in my native language, and doctors often didn’t understand me well. While thinking of examples where language proficiency is used to judge someone’s capabilities or expertise, I thought of Ban Ki-moon, the 8th Secretary-General of the United Nations. Ban Ki-moon was educated and raised in Korea, so English was not his native language, but his diplomatic skills and global leadership were clearly outstanding. Nevertheless, some critics questioned his expertise based on his English abilities, particularly criticizing his Korean-accented English pronunciation. There were even suggestions that he should receive pronunciation training, despite his use of sophisticated, formal language. This shows how the limitations in linguistic expression can impact the perception of someone with excellent expertise.

When I made a trip to Hong Kong with my friend, who is quite good at speaking the Chinese language, I experienced a similar situation. He is quite good enough at speaking Chinese to interact with local people and to tell what he wants to tell, although he has an accent. But in a local restaurant we went by, when he asked the owner about the payment, the owner looked at us and clearly started laughing in a mocking way, gesturing to the other customer as if asking for a translator. After that, the owner refused to listen to him, showing a displeased expression, and just showed a Google Translate screen in his face, gesturing for him to speak into it. Because he hadn’t received that kind of treatment anywhere else, it was clear that the owner was looking down on him, seemingly mocking his accent.

First of all, I would like to say thank you for the interesting article about the accent discrimination. I felt so sad when reading it. Fortunately, I haven’t witnessed that similat case in my life so far since I went to Sydney, maybe the situation has positively changed I hope. However, it is still understandable sadly when some people are treated poorly by their accent. In terms of performance and perception in language proficiency, I would prefer to bring up my own experience in my daily life. I am exposed to various kinds of people coming from many countries in the world due to my job, and most of them are Korean who are not fluent in English. To my perception, an English conversation must be correctly in Grammar and the clasification of vocabularies, however, I am so amazed that my assumption is a bit wrong as we communicate with each other in their humble English (My English is still humble by the way) but somehow our conversations are still successful. Then I realized it depends largely on how we perform and how we try to express our emotion in order to get the other one understood what we want to deliver to. That’s why I believe that the performance in English and our own perception about the perfect English are different to some extent when it comes to communication.

One of my Asian friends, who was looking for a part-time job to make some extra money and support her living expenses in Sydney as an international student, applied for numerous positions over the course of almost a year. However, she was unable to secure any job before she left Sydney. I knew her English proficiency wasn’t as strong as that of native speakers, but she couldn’t even get jobs that didn’t require conversational skills.

At first, we thought it was due to her language skills. But after we saw that a white person, whose English proficiency wasn’t better than my friend’s, was hired for a position she applied for, we realized there was another issue—racial discrimination. So, the problem wasn’t just her English proficiency, but also her race, which made it difficult for Asian students to get proper jobs in Western countries.

Although I studied English for my bachelor’s degree, there are still some things that I just learned after moving to Australia. I often feel a pressure, a fear of not being understood when speaking English with native speakers. This has nothing to do with the people I’ve talked to. They’re all very kind and understanding! Perhaps, I was projecting myself into the unfortunate people facing language-based discrimination from all the stories I heard and news I watched. Unfortunately, this fear sometimes actually affects my confidence in speaking English. It makes me nervous. Unlike writing, where I can take my time to think and plan what I want to deliver, speaking requires me to do it spontaneously.

I really hope we can all work together to create a world where people are not judged based on their second language proficiency.

Faysal’s story left me with a rather sad feeling about how the impact of language barriers has unintentionally affected someone’s life. According to my personal experience, as an international student, I was quite confident with my accent that I have utilized in my home country. However, that situation made me shocked when I used my own accent when I came to Australia and ordered a drink at Starbucks coffee shop. It took a while and the staff still did not understand what I wanted. That experience made me think a lot about my English abilities, not only about how to express my language but also about my accent, whether it was suitable for the communication environment in Australia or not. According to the reading, language barriers also greatly affect communication issues, health and employment is one of the common issues among them. Therefore, in order to find a suitable part-time job, I have tried and made a lot of effort to improve my second language, especially English, creating for myself a way of living that integrates and gives me more confidence in my own abilities.

I encountered stereotypes and biases about the Vietnamese accent when I first came to Australia trying to find a rented room. Whenever I talked to the room lender and introduced myself as a Vietnamese, I received a common reaction “Are you really Vietnamese? Your accent is not like you are one.” They explained that most of the Vietnamese people they met had poor accents with no intonation, so they assumed that someone with proficient English could not come from Vietnam. I was shocked hearing that explanation and felt quite offended by that stereotype. Though it is true that some Vietnamese people have a quite heavy accent that is hard to understand, I do not think that a different (or unique, depending on the way we look at it) accent should become a biased perception of a certain group of people and offensively distinguish them from other communities in an English-dominant country like Australia.

I always wonder why some heartless people work in jobs that really need compassion and understanding. It seems like this goes beyond just language barriers. Sectors like healthcare and professions like doctors and nurses, especially those serving vulnerable populations, really should focus on hiring empathetic people.

I haven’t experienced these issues yet, but I’ve seen a lot of tension around me. Recently, I overheard a librarian at my local community library talking to an old woman who was struggling with English. Instead of being patient and helpful, the librarian was frustrated and aggressive, which left the woman looking intimidated and constantly apologizing.

Another example is my brother, who’s studying here and learning English. He’s trying to do everything from the scratch by himself, like job hunting, and I also overheard that he was talking to an Uber rep, he got an unkind response. The rep ended the call dismissively, saying, “It’s obvious, okay? Just do this, do that, and learn English, okay?”

Last week I visited an elderly Chinese woman in a nursing home who had suffered a stroke and was completely immobile. She only speaks Chinese, and she told me that the nursing staff can only communicate with her through the mobile translation software, but I think the translation software sometimes does not translate accurately, and even misses some important information. In Australia, there is indeed a translation service at the time of visit, which is very helpful for patients who do not speak the language. However, as a country of immigrants, Australia actually has room for improvement, and more people with language barriers should be better guaranteed medical communication.

It’s breathtaking what happened to Fysal. This tragedy could have been avoided if someone had simply tried to understand him.

As a native Spanish speaker, I often feel out of place. I speak English well (for a Spanish speaker), but I’ve received comments like, “You have such an American accent,” or “Why is your accent better than mine?” When I worked in a corporate café, I had a coworker from Mexico who would often make this comment, “You’re not native; speak to me in Spanish,” whenever I spoke English in front of others who didn’t understand Spanish. That made me feel uncomfortable, especially in front of our peers.

I know I have an accent, but I strive to use appropriate English. Interestingly, in Spanish, we don’t differentiate between the “B” and “V” sounds as in English. While I understand the differences and try to pronounce them correctly, native English speakers sometimes correct me. I don’t take it personally, as I appreciate the opportunity to learn, but it can be challenging given my background.

Lastly, I had a good friend from Korea who was an advanced student with outstanding writing, listening, and reading skills. However, her speaking wasn’t perfect, and her accent was quite strong. Unfortunately, this impeded her job search in her field, and she ultimately decided to return to Korea.

Language is only a means of communication; it is not superior to mankind. Since English has taken over as the primary language, proficiency in the language has been used to gauge one’s level of competence. You will be treated and answered well if you can speak English with a good accent, otherwise you will be ignored and labeled as an educated idiot. Fortunately, I haven’t had the opportunity to encounter that kind of treatment in Australia, perhaps this because English is everyone’s second language at my workplace, but i have met many people particularly from China and India, who find it extremely difficult to fit in with Australian society because of language Barriers even if they are competent and qualified person.

It makes me sad when reading Faysal’s case and knowing the unfair treatment he received from the health provider. I believe that many people coming to Australia from other countries would experience the same problem, especially those with a NESB. Faysal’s story reminds me of my friend who works as an all-rounder at a coffee shop where he has to take orders and do customer service. On his very first working days, he made mistakes when taking orders from customers as he could not understand what they were saying, especially when they had some important notice for their drinks. This caused him many interruptions at work as his co-workers made drinks with the wrong recipe, making customers dissatisfied with his coffee shop’s service. One thing that is really irritating is that he was forced to quit the job because the boss told him that he was not qualified for this position.

Reading the story of Ahmed and realizing that this man could have been saved easily if it was not for linguistic discrimination is truly heartbreaking, but more than anything it shows us that the system needs some drastic changes.

Although I have never experienced or heard of a situation this tragic in my social circle, I am fully aware of the fact that speakers of lower proficiency often suffer exclusion and negative reactions in social interactions. In my beginning stages of learning to speak Spanish, I was frequently interrupted or simply overlooked by certain members of groups. It was frustrating to see how my efforts were not appreciated at all, simply because these people have never gone through the same process. For a while I even considered quitting my language learning journey due to these negative experiences. Even though mine is not a severe case of linguistic discrimination and, thankfully, ended well, I understand the struggles involved in being judged based on one’s accent or speaking skills and I am doing my best to work effectively against it in my private life and social encounters.

My experience from 6 years ago when I started looking for a job has been that of overperforming against the perception of my audience. As a brown, aspiring teacher in Australia, I remember going to a private language school to drop my resume and the lady at the reception assumed I was there to enquire about an English course because of my appearance. She looked surprised when I enquired about vacancies and more so with how I spoke! I felt an immediate underestimation because of my colour- a case of seeing overrides what we hear. Another case is when an interviewer openly told me that he did not expect someone from my background to be so fluent and he asked me “What did you do differently?” in trying to understand the foundation of my proficiency given that I’m from India which he had a very outdated and uninformed grasp of.

English language teaching surprisingly often is a real bastion of nativist and racist attitudes 🙁

My friend is from northern China, and their dialect has a very heavy accent, which affects the way she accents every syllable of a word when she speaks English. Although she is very fluent in English, her accent is so pronounced that when she speaks to others. And they often miss what she is saying and only remember her accent. I remember when she made a complex suggestion in our group discussion, and even though I thought she had articulated it clearly, one of the group members stood up and repeated her point with a different word and asked, “Is that what you meant?” This action confused both her and me, as we realized that the problem was not language proficiency, but rather the fact that accents influence people’s judgment of your professional competence. I am keenly aware that people’s attitudes towards different accents can lead to prejudice against you. It’s true though, there are times when you can’t change others, you can only change yourself. But accents do make people feel inferior TT.

Reading the blog post, I reminded myself of a Korean friend of mine who recently got sacked from her part-time place. She was working in a place mostly consisting of other East Asian workers, who were all a lot more experienced than her with the job. The reason for her being fired, allegedly, was her “rudeness” to the fellow workers. She was a cashier, and the boss said he heard a lot of complaints that she was rude to her customers and colleagues. She told me the other day about one of the negative feedback she got from them, as the manager said “When people teach you, don’t say “I got it.”. It means you know everything, and you don’t. That’s why people don’t feel like training you anymore.” When I heard this from her, I was aghast. “What does that ever mean? “I got it” means you understand, it doesn’t mean you know everything!” She shrugged her shoulders. “Maybe they were from East Asia where women are more docile. Maybe they expected me to be more docile, and didn’t like my English accent that is more westernized than theirs.” Her comment was equally puzzling, and I held back a heavy heart to my home that day. Thinking about it again, I understood. Their language has a longer vowel sound at the end of every sentence, like Kap-cun-caa—-. To their ears, the newbie’s accent and her English command could not have sounded warm enough. True, I don’t know the facial expression or the intonation she bore in the store. Maybe she was not a service sector material. But the way she was misunderstood, I thought, got off on the wrong foot both gender and culture-wise. I saw a lot of cashiers from the West who wore a lot more indifference on their faces and fewer smiles and brusque accents, but I was wondering, would they be fired for that reason? How does ‘I got it’ translate into something with such malicious intention? I was furious for her and said it was against the labor law, but she wanted to trouble in this country. Speaking English better than the group can be detrimental. It’s a matter of power and hierarchy, not proficiency. She was better taught than her fellows, and that could have hurt their egos. There could be much more explanation for the cause of this incident, but one thing was clear to me: There was little justice or right or wrong in that dismissal. She was a new, female employee foreign to the group. She did not quite yet belong, and she ‘should have acted more pliant’ until she was admitted to the group. Lesson well learned.

🙁

For example, I have one friend who came from Republic of South Africa and he has been living more than 10 years. He feels really frustrated and embarrassed when asked a questions like “How long have you been here in South Korea?” by someone. For me his Korean is good for casual conversation but he kind of feels shamed about his Korean pronunciation and accent. I think he is affected by Korean’s high expectation. He once told me that his coworker had said that his Korean proficiency was poor comparing with other native speakers working at school. I am pretty sure that the coworker had never been in a place he had to keep using a new language for living and working.

That’s exactly the thing: most people who are rude to migrants and make language learners feel small have never had the experience, and have no idea how much courage and resilience and perseverance it takes to make a new life in a new country …

Hello, Ingrid. I am sad to hear that the man was ignored by the nurse’s assumption that he was fake sick and ended up to his death. As you wrote, it takes double effort for NESB speakers to deliver his or her symptoms to doctors or nurses in a medium of English because they sometimes feel overwhelmed by unfamiliar situation and not familiar with a certain medical words. After reading your article, I start to think the situation when speakers with a limited proficiency are sometimes considered less important and less serious. As you point out, most of people who believe in that way are monolingual because they are born and raised without a need to learn a new language so they don’t know how challenging to do that. In South Korea, I have seen the similar premise that if foreign speakers are fluent in Korean, they are considered highly smart and intelligent. If they are less fluent in Korea, they are to blame easily especially if they live in South Korean more than 10 years. Surely it’s wrong but it seems that there is a prominent premise that people’s intelligence or value can get judged by their second language proficiency.

It is so sad to hear the tragic story of Ahmed. He could have been saved if any of his doctors took seriously what he told them. In my observation, if people cannot speak English well in Australia, it is hard for them to find a decent job here. For example, among Chinese, we are always warned not to work for Chinese employers in Australia as the pay will be very low. However, for those who have limited English ability have no chance but to work there to make a living, which put them at risk of exploitation.

On the other hand, for those people who have accents in their English, most of them feel embarrassed to speak to others, which makes them isolated from the community.

It is assumed that all people come to Australia should have a good level of English proficiency, but this is not true.

When my friend moved to Australia, she faced a tough time with her English, even though it was understandable. Her Thai accent sometimes caused confusion, especially with her non-Asian coworkers at the café where she worked. In the beginning, they would ask her to repeat herself, and the harshest comment she got was, “Go learn English.” It really shook her confidence. But despite feeling discouraged, she kept pushing herself to improve. Over time, she adjusted to the new environment and became great at her job. Her experience shows how hard it can be when others focus more on accents than the actual ability to communicate.

As someone with a heavy accent, I find myself very relatable to this article, especially with the idea of being mistreated because of the NESB features in my English. A few years ago, I had a negative experience at a tailor shop when I had to take measurements for my outfit. I noticed that the shop assistant was uncomfortable with me and my accent through certain choices of language use like purposefully using broken English to talk to me or constantly repeating questions despite my ability to listen and comprehend everything they said. It was very disappointing that I was judged by my voice and appearance rather than my abilities or personality. That negative experience has changed the way I use English in my social life since then. Nowadays, I try to pay constant attention to my pronunciation and speed of speech to avoid being perceived as “rude” or “annoying”.

After arriving here in Australia, I needed to find jobs to maintain my financial conditions. So,I happen to visit lots of Hotels, Restaurants, Super shop and many other places.Whenever i started talking with the manager or the person in charge, i felt a nit nervous though my English wasn’t very bad.Another thing is, the people i was talking to also had a fixed perception that a person like me can’t have a good proficiency in English and some of them also asked about my IELTS score and so on.Now i happen to have a job in a 4 star hotel where the chefs are from different countries and their English is nor very proficient. So we can’t understand each other’s response clearly whenever we engage in a conversation. Nowadays, I always feel a tension in my subconscious mind while I am talking with anyone using English about making mistakes and that also is creating a barrier for me to express myself properly.

Luckily, I personally did not encounter similar situations when I arrived in Australia last year. However, the Australian accent was very new to me, and sometimes I struggled to understand the speakers. I often asked for repetition or clarification, and most of the time, people were understanding. However, there were occasions when they appeared frustrated, which made those moments a bit awkward for me. I should say, as an Iranian woman, I feel safer and more respected here. While being a woman is not directly related to language, I believe people are generally more tolerant and respectful towards women in Australia, at least compared to my home country, Iran. Unfortunately, I have witnessed three instances of discrimination and disrespectful behaviour towards Asian people, which seems significant in just a year. One incident occurred on the train when a boy refused to let another Asian boy sit next to him, asking him to change seats, while another woman respectfully accepted the seat beside him. Such behaviour should not happen anywhere in the world. I totally understand how this boy felt because I have experienced discrimination myself in my own country. For example, if you wear a so-called “improper” hijab, some women might ask you to leave a place or adjust your hijab as they see fit. Unfortunately, these ideologies still exist in the 21st century, and I hope that more people learn to understand and respect different lifestyles and backgrounds in the near future.

Fortunately, I haven’t personally experienced these tensions, but I’ve certainly witnessed them, especially among Indian international students in Australia. Many of these students are fluent in English, but their accents often lead to unfair judgments. In academic settings, they are sometimes viewed as less capable or hardworking simply because of how they sound, resulting in biased assessments. I’ve also noticed similar challenges in the workplace, where non-native English-speaking staff are sometimes dismissed or misunderstood, even when their performance is unaffected by their language or accent.

It’s particularly sad to see some international students hesitate to make basic purchases, worried they won’t be understood or taken seriously. For instance, I once saw a student trying to order coffee, and the person behind the counter kept yelling at him to speak louder and more clearly, which came across as rude. This disconnect between actual ability and perceived competence highlights a persistent and unfortunate bias.

Thanks, Liz! It’s these little everyday discriminations, like the coffee order you describe, that can ruin your joy and confidence. We saw a lot of that in the research for Life in a New Language. The good news is that, over time, most participants were able to build a sense of belonging and home.

This entry had so many powerful notes on perceptions of power that I remembered more than a couple of experiences where a person’s worth was “measured” by their language skills and their language performance on the surface, but what was really being considered was their not-being-white or not-passing-as-white nature. Most of those experiences happened in my working environment. I overheard my bosses talking about how they couldn’t hire a Colombian teacher because her accent was too strong. How she selected one teacher from Venezuela and me to go on an excursion with some Japanese students but we were asked not to speak in our mother tongues so students’ wouldn’t notice where we come from. However, those same bosses were against those perceptions saying it was because the students were “customers” and customers are racist. We fall into those racist dynamics where we have to hide and we believe it is a matter of not being native because we teach English, but it might as well be more about not being from this dominant culture.

Thanks, Daniela! So easy to hide racism in ELT behind the assertion that students are racist …

As a business lecturer in Vietnam, I observe that students from various regions bring diverse dialects and language backgrounds, which can create significant challenges in class. Students with regional accents sometimes hesitate to express themselves, fearing they might be undervalued, which impacts their confidence and participation. I also feel a personal conflict when my efforts to help them overcome these barriers seem insufficient.

To foster an inclusive learning environment, I’ve been employing innovative teaching methods. Multicultural group activities encourage students to collaborate, gradually fostering openness and mutual learning. Using multimedia resources like videos and visuals aids comprehension and eases language pressure. A feedback approach centered on ideas rather than language accuracy helps students recognize their worth and build confidence.

These methods not only empower all students to express themselves but also contribute to a learning space where linguistic and cultural diversity is respected. While not entirely removing all barriers, I’ve seen students learn to integrate and respect one another, enhancing their learning experience and communication skills for all. Yet, it raises an essential question: Can a student truly reach their full potential if they must always hide their hometown accent?

Education really is a privileged space to break down barriers. Students who learn to be comfortable in class surely are more open IRL, too.

It is deeply upsetting to read about Faysal’s experience and the inadequate treatment he received from his care provider. His story reminds me of my friend’s situation, and I believe many individuals in Australia face similar challenges today. In 2019, my friend, a new international student, faced difficulties when seeking medical care due to a back issue. However, she struggled in speaking and had difficulty understanding what the doctor’s instructions and explanations. This language barrier not only affected her confidence but also hindered her interaction with native speakers. As a result, she becomes less open when talking to new people, especially if they are from English-speaking countries. Due to the ongoing communication struggles, she had to visit the care provider multiple times and always relied on a friend to accompany her as an interpreter.

In my situation, my performance was judged not by my ability but by superficial factors such as my appearance and background. Although this experience wasn’t solely about my language skills, it clearly shows a conflict between how well I performed and how I was perceived. I worked as a manager at a language a school, and the CEO never wanted me to appear in any promotional brochures or videos because I look Asian. He also told me not to hire any more Asian-looking teachers because we already had 2. During my farewell, he made a comment that although I was not born in Australia and English was not my first language, I was a good teacher and manager. I felt quite uncomfortable with the comment, but I didn’t way anything because I didn’t want to make things awkward. However, if I come across this situation again, I don’t think I will be silent again.

After moving to Australia, I have also experienced how a person’s accent can overshadow their actual language skills. It is frustrating to be judged based on how I sound rather than what I say. Sometimes, asking someone to repeat themselves feels daunting because I can sense that they perceive me as less proficient, even when my grammar is correct. The pressure to speak like a native speaker creates a sense of frustration, as my accent often defines my identity rather than my ability to communicate effectively.

Additionally, I believe that language proficiency is assessed differently in various situations. For instance, a high IELTS score does not necessarily mean someone can navigate daily conversations successfully. In real-life interactions, understanding cultural nuances and non-verbal cues is just as important. It is interesting to see how a British accent can be valued highly while others struggle to be taken seriously. By acknowledging these disparities, we can foster a more inclusive understanding of language proficiency as a dynamic interplay between performance and perception.

Faysal’s story is almost the norm and experienced by most migrants in Australia. I arrived in Australia as a skilled migrant with a Masters and several years of rich experience overseas. I had taught in international schools overseas for over 10 years but when I appied for English teacher roles, I would not even be offered an interview. Despite my CV being eloquent my brown skin and my name, “Venkataramanan” stood in the way. Employers couldn’t fathom how someone with such a name could teach English. In their perception, people with such names could teach Maths or Science, but English, no way! I decided to do a Dip ED which had a practicuum placement in a school. Post my practicuum, I was immediately offered a job at the same school and they were surprised that with my teaching skills and experience, I had never got an interview before. Due to the negative perception of my name and a judgement of my abilities thereon, I had not even got an opportunity to display my skills.

I think everyone who comes in an English-speaking country (or another) with a different first language, even after passing out the required language proficiency, faces tensions like this. Before coming to Australia, I was so confident with my English Language but here, besides getting confused with accents, I started doubting myself if I am speaking right because mostly, I was told to repeat my say and I always tried to repeat by paraphrasing the sentence. But gradually I understood that I’m not speaking wrong but the next person isn’t perceiving as I am saying.

Sometimes it also happened that I couldn’t understand the whole sentence what the next person is speaking, but to avoid bothering the speaker by repetition, I responded only by perceiving and analyzing the root words, accent or hand gestures, So, I think performance and perception in communications plays a great role and sometimes it can also lead to severe results as happened with Faysal.

While reading it, I could not stop thinking of my ex-coworker. Although it was shameful and embarrassing, but I would like to share my experience. I was a tutor teaching English as a foreign language in my country. I was looking for a partner who was in charge of speaking and writing part as a native speaker. I had 2 applicants. One is a typical Caucasian. He was from the State and had no degree. He is a person who wants to make money easily just by speaking his language. He was lazy and didn’t prepare for class at all. I fired him and hired another person. The other person was from the Philippines, and she was a well-educated person. She had a degree in Literature and Education. I decided to work with her. She had high proficiency in English. However, the students’ parents complained to me about changing the teacher. Language proficiency, appearance, or nationality should be seen as separate, but the real world is not yet. Even from the same country, preference can vary depending on skin color, white or not. We should know that others can judge or evaluate us in the same way. I think that we still needed to learn to embrace differences and how to respect others.

This reminds me of a situation I experienced when I went to India as an overseas volunteer in 2018. As a recent graduate, I was eager to improve my English and gain new life experiences. However, the program was founded by Koreans, and most of the other overseas volunteers were also from Korea. Although we used English as the medium for activities and camps, there was a time when we had to gather and discuss our performance.

During these discussions, the Korean leaders mainly spoke in Korean with the volunteers, briefly switching to English before continuing in Korean. They explained that some Korean volunteers didn’t understand English well and needed support. While I could understand some Korean, my Thai friends couldn’t, leaving us feeling excluded from sharing our ideas and opinions, and like minorities in the group.

This experience demonstrated how language barriers can lead to exclusion, even with a shared language. It reinforces the point that language proficiency is about creating an inclusive environment where everyone can participate and feel valued.

Thank you for sharing this story. It reminds me of when I joined a work and travel program in America with my friends 3 years ago. We worked at a pizza restaurant with a diverse group of employees and customers, but most of them were Americans. One day, after my friends and I finished work and closed the restaurant, a group of American teenagers asked us to buy pizza. However, my friend told them that they couldn’t buy it because the restaurant was closing, but they didn’t believe her and made fun of her accent. In fact, she speaks English well, but her accent was different from a native speaker’s, so they made fun of her just because she was Asian. After that, they went to ask one of my colleagues who was a native to buy a pizza again, but they received the same answer. Thus, it made them irritated and turned to make slant-eye gestures and spoke Chinese to me, which is a highly inappropriate form of racism. However, we didn’t say anything to avoid conflict.

This experience reminded me of the importance of focusing on communication ability rather than accent or other factors. Judging or make fun language ability based on bias external factors can really undermine that person’s speaking confidence.

It’s heartbreaking to read about Faysal and what happened to him. I’m also surprised that a lot of people in the comments said that they faced some kind of racism or discrimination based on their accent, language proficiency or even their outlook.

Sadly, Faysal’s story is an example on how language differences can create barriers to access different services or to be taken seriously not only in the healthcare sector but in different aspects and situations. And I, like other students or emigrants can relate to the feeling of not being taken seriously because of an accent or language proficiency.

My pronunciation has always made me feel self-conscious, and sometimes I get the impression that nobody will listen to me or appreciate what I have to say. I think that we need to be more kind and aware of our own biases also truly listen to everyone, regardless of how they speak.

When I first came to Australia, I was eager to connect with the youth community in my local church. However, I quickly discovered an issue between my perceived English level and my ability to make small talks with people. Even though I knew I had a pretty good understanding of English, I found every casual conversation terrifying. Every time I made a mistake, mispronounced a word, or failed to understand the meaning of a joke, I felt less and less confident. However, I slowly began to understand that being able to speak a language is not only a matter of mastering grammar rules. Creating a conversation and making small talk requires plenty of knowledge and practice. I also believe that my biggest discovery here is that I can make mistakes or fail to understand a joke and everything is going to be okay.

Such important lessons! And hopefully your church group are an inclusive bunch of people! 🙂

I attended an Australian high school with a large number of Chinese students, and something that I often noticed, particularly in places like Chatswood with a large Chinese population, was that shopkeepers would often engage with these students by first speaking in Mandarin. However, as second-generation migrants, many of these students did not have enough proficiency or confidence in using Mandarin to be able to interact in the language. Many of these students would in fact describe themselves as English monolinguals; in reality, the majority had relatively high Mandarin listening proficiency, but relatively low speaking proficiency. This would sometimes lead to some tensions when the students answered questions in English to people who were clearly expecting to communicate in Mandarin. It would also, at times, result in tensions when interacting with their parents who often held expectations that their children would learn their heritage language.

Just knowing what happened with Faysal breaks my heart. Because English is not his native language, he didn’t deserve this.

Unfortunately, when I first arrived in Sydney, I had a similar experience of racism. I was traveling by train for some grocery shopping and trust me, Ingrid, I was just quietly sitting on the train. Out of nowhere a middle-aged woman came to me and started shouting saying ‘Bloody Asians’ for no reason at all. I could have responded to her, but I chose to remain silent because I was so terrified of her actions.

But I agree with the part where you said “Australians who speak English as their first language have fewer and fewer opportunities to learn another language and hence are poorly equipped to relate to the challenges of language learning.” To your knowledge, I am proficient in Bangla, my mother language, Hindi, English, and a little bit of Korean. As an international student, I’m doing my best to cope with things on my own in a foreign country, and I believe it’s time for people to stop making assumptions about others or offering services based only on their accents.

So sorry this happened to you! One of our participants in the Life in a New Language project had a similar experience, and his response was “This is Indigenous land. Guests who come first, go first.” – even if it may be wiser to stay silent, as you did, it’s important to keep this truth: all non-Indigenous people are migrants to this land.

When I came to Australia, I realised English was not my issue. My English proficiency was enough for me to communicate in daily life, and there were some difficulties when using English for academic purposes, but I still can handle it. However, the problem arose when I was in the foundation course. Our group in class were formed randomly; I had to do group work with three Chinese girls. What annoyed me the most was that during the discussion, they kept talking with each other in Chinese, not English. When they had something to inform me, they talked to me two sentences in English and continued to speak Chinese together. Of course, I don’t know Chinese so that I couldn’t join the discussion. I complained to them, and later on, they did speak English a little bit, but then they turned back to Chinese. And the use of language like that makes me feel isolated and not respectful. Some of my friends told me that she talked to Chinese people, and they told her that they didn’t mean to discriminate against anyone; it was just like they were crowded, and communicating in the mother language was more convenient. I hope so, but personally, I think that when people come to Australia, which is an English-speaking country, English should be used as both a communication tool and a lingual franca, not their mother tongue.

Of course, not all Chinese I meet here are like that, but I was surprised when my language proficiency problem in Australia was Chinese, the language I didn’t know entirely, instead of English.

Fortunately, I have not had serious problems such as discrimination in Australia. However, I remembered my experience in my country.

One day, I took an express train. All seats are reserved and my seat was between Westerners (a girl (window seat: my left side) and her father (aisle seat: my right side)). I thought the father wanted to sit next to his daughter, so I suggested to him that we change our seats in English. Surprisingly, he answered me in my language. “My daughter wants to enjoy the scenery but I like an aisle seat, so the current seat is preferable.” His pronunciation was really well. I noticed I had misunderstood two things, namely, his language proficiency and preference.

After that, I try not to relate people’s appearance to their ability and preference. Also, I hope my English proficiency is not judged from my Asian appearance.

After reading this article, I feel deeply moved. During my two years of studying in Australia, I faced many similar situations, particularly in the first half of my MBA program. Each course involved group presentations with four or five people. Most local students studied part-time, while international students like me were full-time. I often felt like the youngest, as many classmates had extensive work experience. Initially, my limited English proficiency led to painful experiences. Some classmates complained about my English, and a few even refused to work with me. Reflecting on that time, I felt sad because they lacked an inclusive attitude towards me. However, these challenges motivated me to improve my English. After graduating from my MBA, I continued to pursue a degree in translation, hoping to further enhance my language skills.

And in the process you are gaining a valuable dual qualification 🙂 Good on you for being resilient and agile!

Dear Ingrid,

I am lucky I haven’t encountered any discrimination or unjust treatment in Australia so far. But your article reminded me of the monolingual mindset in Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, the major language is Cantonese. Nowadays, many Mandarin speakers from mainland China have moved to Hong Kong. Many of them struggle to find a job, receive a relatively lower salary or are unfairly perceived as less intelligent only because they cannot speak fluent Cantonese.

There are also many ethnic minorities born and raised in Hong Kong such as Indian, Indonesian and Pilipino. They can speak fluent Cantonese but with accent. Still, Hong Kong people do not fully accept them as Hongkonger and will use some derogatory term in Cantonese to call them. On the other hand, our “imaginary enemy”, Singapore, has been doing a good job to become a very inclusive and diverse country. It saddens me that many people in Hong Kong still hold such narrow views.

DM

Thanks, DM! Australia certainly doesn’t hold a monopoly on bigotry …

When I lived in an English-speaking country, I faced discrimination based on my race as well as my non-English-speaking background. Sometimes, customers did not understand what I was saying when working at a cafe; I often got requests to speak to my white colleague. At first, I thought this was because my English was not perfect. I studied a lot to address this problem. However, after finding that the colleague came from Italy, which was not an English-speaking country, and her English was not perfect as well, I realized that it was racism. It was frustrating as it meant I could not improve the situation. I lost confidence whenever people asked me to repeat what I said. It also negatively affected my performance. Although my role was providing customer service, I feared conversation. Now, I try to be confident, as I believe speaking a second language is an advanced skill.

The tension between language proficiency perception and performance is seen in Australia, a linguistically diverse environment. From my personal experience the talented people from non-English speaking background or “Migrantes” in Australia being viewed as less capable only because of their accents. They assume that the colour of the skin means we should have a bad English. For example: my husband is a lawyer from Bangladesh, also have degrees from Uk but still struggling to get a job here because he is facing bias in Australian job interviews. His interviewers doubted him even though he answered effectively, showing how accents can unjustly influence assessments of competence. Even one interviewer said to him that he was surprised that how my husband’s English is that good. This reflects how societal biases are seen as a marker of inferiority rather than doing a good job.

so sorry to hear this happened to your husband! Without a doubt, work is unfortunately the domain where negative stereotypes have the greatest effect in maintaining social inequality in Australia

One day, I witnessed a passenger on the bus asking the bus driver about the bus route. The passenger appeared to be of Asian descent. The driver responded vaguely, seemingly unable to understand the passenger’s question, and failed to provide accurate information. Moreover, he used rude expressions like “Come in! Sit down!” as if he was ignoring the passenger. While I cannot accurately assess the passenger’s language skills, I believe it would not have been very difficult for the driver to understand him. Since the passenger was asking about a specific location, the passenger’s English proficiency likely did not play a significant role. However, the driver treated him disrespectfully due to his slightly hesitant speech. I was quite shocked when the driver shouted at him to “come in and sit down!”

For a few years, I worked as a language teacher at a small English language school in a French speaking country. The school’s founder and owner, who is also a qualified language teacher, is a native English speaker from Australia. We used to get along well and maintained a friendly relationship throughout my time there. Based on my credentials and English language proficiency, she had decided that I was a good fit for the job. However, before starting teaching, she advised me not to reveal my non-English-speaking background as students would have questioned my suitability and more importantly credibility as an English language teacher. It is a shame that NESB qualified teachers are not perceived as competent as their native English-speaking counterparts. Multilingual professionals should be given as much credit as native speaking teachers.

When people migrate to a different country, they need to consider it carefully due to the various difficulties they might face. The language barrier can lead to serious issues, such as hindering access to medical assistance. Additionally, they might struggle with preserving and passing on their own culture to the next generations. Moving to a different country is undoubtedly a significant decision, but language is a language that we can acquire and overcome the barrier by learning as people could in the 18th century without any technology.

In my workplace, we have a diverse staff of different nationalities. When some employees speak in their native language, I can’t understand at all. However, we manage to communicate effectively in English. We also share basic words from different languages, enabling us to learn from each other, which I always find interesting. I simply thought if there was only one language in the world, people could exchange anything easily, but it sounds boring like no color.

The conflict between performance and perception in language proficiency is a widespread issue that I have personally observed in a variety of circumstances. However, the problem is important to the larger debate. I’ve observed people with exceptional language skills who are sometimes misjudged or rejected by others who perceive them as less skilled because of their non-native accents. This perception bias frequently results in missed opportunities, discrimination, or the idea that the individual is less intelligent or capable. It is critical to note that language ability extends beyond grammatical correctness to include understanding languages and other communication styles. This issue highlights the need for both individuals and institutions to be more inclusive and sympathetic, knowing that language proficiency is produced collaboratively in social interactions. We can create a more inclusive society where everyone has equal opportunities and their skills are not veiled by linguistic differences by addressing these perceived discriminations and investing in language support.

That’s right, Daisy – we can do it 🙂

After professor Ingrid presented about the McGurk effect, an audio-visual speech illusion that demonstrates the impact of visual cues on speech perception and relevant experimental research – “Seeing Asians speaking English” conducted by Donald Rubin in 1992, I have acknowledged that the McGurk effect influences the perception of ‘Native speaker’ teachers are valued more than ‘Non-native’ teachers and it is kind of natural phenomenon, not racism or discrimination. It was really eye-opener for me to think about some common perceptions in a different way. Therefore, now I am thinking that ‘Non-native’ language teachers may better to concentrate on justifying their proficiency through their pedagogy, classroom management techniques, adaptability, creativity and empathy etc rather than fighting against the misconception or complaining.

Thanks, Undraa! Reminds me of the serenity prayer “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; the courage to change the things I can; and the wisdom to know the difference.” – I think that’s a good motto for many things in life …

Definitely, it is a great motto to keep in mind. Sometimes, it is better to let things just be. 🙂

This is a very eye-opening story of the barriers migrants go through after seeking a different life in a different location. Most of us did not know what to expect until we actually experienced a challenge in communication and its consequences. I have already shared the story of me on my first week, not knowing to press that STOP button on the bus. I did not ask anyone for help because the idea of not knowing something a child might easily know can be very embarrassing for an adult. Another narrative is from my cousin, who is a successful Civil engineer leading a team in one of the biggest construction companies in Sydney. She told me that in her first year as an engineer, she had to record all meetings and spend time at home to decode all the information shared and this affected her confidence drastically. She came to this realisation only after a time, that she doing her job in a second language, only makes her more capable than any monolingual employee in the office. Another interaction of mine was with a Chinese old man, who used Google Translate for communication. I realised that he tried translating the simple English word “ok” to communicate with me and I could not help but think how his lack of confidence in performing language has caused him not to believe in himself and his knowledge to this extent and the reasons that might have caused this! Thanks for reading my comment.

Oh – having to rely on Google translate to say “ok” is pretty sad 🙁 … but maybe he tried to say something more complicated and simply gave up? …

Hi Ingrid, I do think he knew that ok is ok in both languages but anyway maybe not at that moment because his confidence was extremely boosted down?

I would like to look into the subject of linguistic barriers further here.

Please don’t miss the cute picture of the cat and dig trying to communicate in my resource:)

As we all know, when communicating, language can be non-verbal, such as through signs, body language, or facial expressions, or verbal, such as using words to read, write, and talk. However, sometimes even with all of that, communication cannot be properly done and the message will not be conveyed. These barriers include cultural diversities, ambiguity in communication and language barriers. Different types of language barriers are: foreign language, accents, dialects, pidgin, jargon and slang, word choice, literacy, or grammar.

Here are some suggestions for overcoming linguistic barriers::

To prevent ambiguity and verbosity, communicate using language that is straightforward, precise, and concise is a good idea. To cut down on mistakes in writing and speech, using grammar and spell-checking applications can be helpful. At last, the only way to break a linguistic barrier is to gain linguistic proficiency as it’s critical to be proficient in the language you use for successful communication.

I would like to add that it is important for learners and migrants to know that most people are patient and it is absolutely okay to make mistakes.

https://www.communicationtheory.org/language-barriers-in-communication/

Hehe … you have a much better article on language barriers right here in Language on the Move: https://languageonthemove.com/language-barriers-to-social-participation/

This is such a tragic story but I witness versions of this event in every country I have been in whereby non native language speakers suffer often severe or inconvenient consequences based on the biased misperceptions of others. I have experienced this myself many times and this has helped me develop compassion for students and people I meet struggling linguistically. This has helped me to become a better language teacher and friend. In Australia I routinely come across people struggling to be understood in English although I understand them perfectly. The person they are attempting to communicate with appears to not even be trying to listen and understand. For successful communication to happen both parties firstly need to want to communicate, that is key. I have found that even if both parties speak not one word of a language in common, but want to communicate, they can fairly easily do so to some degree. I have noticed that when people hear my accent when speaking French, they can become quickly dismissive and do not even try to listen to what I am saying. Japanese people see my face and have the same reaction very quickly going to, ” I don’t understand or I don’t speak English”. In Japanese, I have often had to speak slowly and clearly and repeat the sentence : “I am speaking Japanese” before people visibly relax and stat to communicate. Many people are nerpous of people who look or sound different, no matter how care the speaker uses with their communication.

I remember reading about this incident in an article. It breaks my heart but also frustrates me to no end. It is not just our accent that gets judged. You get judged as less worthy before you even open your mouth, just from your appearance. They expect to hear foreign accents or broken English from the very beginning. I wear hijab and have brown skin. It would be a lie to say that my appearance doesn’t get a second glance.