![]() Installment #4 in the mini-series on multilingual signage

Installment #4 in the mini-series on multilingual signage

Toilets as an object of sociolinguistic research?! Not likely?! Think again! Today, I am going to discuss toilet signage as an indicator of how inclusive a society is.

Types of toilets and ways of cleaning yourself after using them are quite diverse internationally – thus, creating the potential for difficulties and misunderstandings in this day and age of mass migration. So, what do you do if you are planning toilet facilities in public spaces that are likely to be used by people from many different backgrounds?

In Australia, and elsewhere in the West, the preference is for a one-size-fits-all approach: public toilets are almost universally of the sit-down-on kind and only paper is provided to clean yourself. This obviously creates difficulties for people used to squat toilets and/or people used to cleaning themselves with water. Public toilets in places with a high migrant population often feature signage to “help” them overcome this problem. I’ve got a large collection of signs such as Sign #1 and Sign #2 from public toilets around the country and I have collected them all in English language schools.

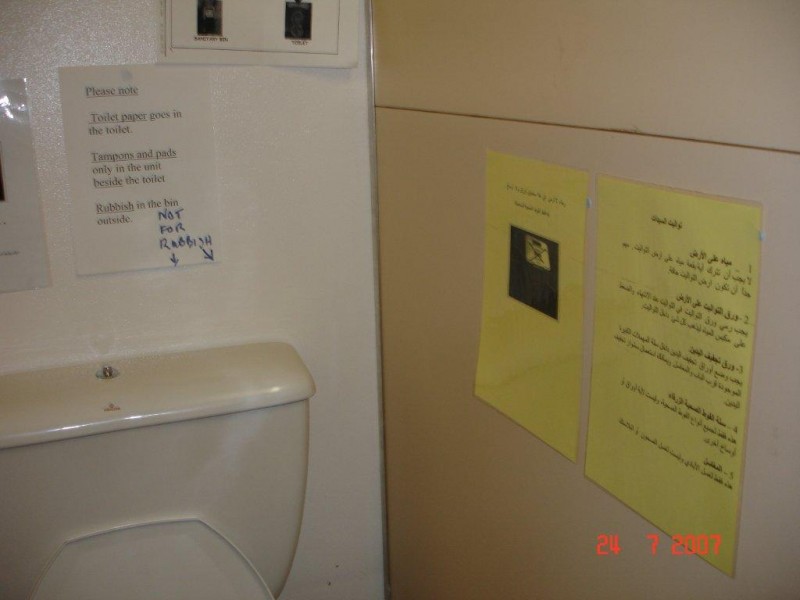

Since the days of the Americanization movement (Pavlenko 2005), English language instruction for migrants has often been guided by the assimilationist impulse: to not only turn them into speakers of English but to also transform them into new kinds of people. In contemporary Australia assimilation is dead at the policy level and has become almost a dirty word. However, the signage in the ladies’ toilets in an English school that mostly caters to migrants (rather than overseas students) in one of metropolitan Sydney’s lower-income suburbs (Signs #3, 4, 5, 6) tells a different story.

Signs #3 and #4 were taken inside a stall and signs #5 and #6 in the common wash area in front of the stalls. What is striking about these signs is their clutter, their urgency and the sheer number of instructions, assertions and prohibitions. The instructions in the stall on where to place toilet paper, tampons and sanitary pads, and other rubbish come in English as well as Arabic, Chinese and Vietnamese. Arabic is singled out for special treatment as it features not only on the trilingual leaflet at the back of the stall but additionally gets two fairly detailed leaflets with further instructions. It is not only the amount of instructions aimed at Arabic speakers that stands out, it is also the fact that Arabic is printed on yellow paper while white paper was used for everything else. I’m pretty sure that whoever put up the signs would not have collected actual evidence that Arabic-speaking women offend against toilet etiquette more than women of any other language background. So, I have to assume that singling out Arabic speakers for special “attention” is based on stereotypes. Personally, I find being singled out in this way alienating and I wonder how Arabic-speaking users of that toilet feel? Do they just ignore the sign? Do they feel humiliated? Angry? Docile?

It is also interesting to note that, for an English language school, there is surprisingly little evidence of an understanding of low-level proficiency in English. While the fact that “toilet paper”, “tampons and pads” and “rubbish” are in three different categories must have seemed self-evident to the writer of the sign (and also the person who added the same message in hand-writing), “rubbish” could easily be interpreted as a general term that includes the other two, making the message confusing and further diluting the power of the sign.

In the wash area outside the toilet stalls, the wall on both sides of the sink and mirror is littered with a veritable plethora of bathroom etiquette: there are the disposal instructions featured in the stalls repeated – in English, as pictograms, and, on separate pieces of paper, again in Arabic and Vietnamese (both languages “color-coded” to make them stand-out even more); additionally, there is a sticker with a non-smoking pictogram, a request to refrain from smoking (“it’s against the law”) printed on paper, a request to wash your hands, a statement that the sink is for hands only and so are the towels, and a prohibition against taking or leaving “water, cups or bottles.” Most of these signs are simple print-outs rather than more durable materials, stuck onto the wall with sticky tape at odd angles. Some of the signs have been splashed with water and become wavy. The waviness of the paper makes it look unhygienic. It should be obvious to anyone that paper is not the material of choice for toilet signage (sticking paper in plastic folders doesn’t help, either: sign #2 is moldy).

The material, the positions and the texts themselves are evidence of makeshift signage and seem suggestive of a passive-aggressive running battle between different groups of users of this toilet. Having to share a toilet with people who leave foot-prints on the toilet seat or water all over the floor is obviously aggravating and, if these fliers, are anything to go by, a recipe for ethnic tensions. However, the way forward in a multicultural, democratic and inclusive society is not the educational – and implicitly assimilationist – impulse evidenced in the signs I have discussed here but choice when it comes to type of toilet used. In the same way that public spaces are required to provide toilets for the disabled and often voluntarily provide mixed-sex family facilities (to cater for fathers with girls or mothers with boys) and sometimes even miniature sit-on toilets for children, there could also be a squat toilet or two in such places. Schools, malls and airports across Asia and the Middle East often offer such choice: stalls with sit-on toilets and stalls with squat toilets and the provision of both paper and a water hose in both allowing travelers the flexibility of choice. Surely, we can offer the same choice in the West. It would be a concrete step towards social inclusion and we would no longer need the unpleasant signs I have discussed here.

![]() Pavlenko, Aneta (2005). ‘Ask Each Pupil About Her Methods of Cleaning’: Ideologies of Language and Gender in Americanisation Instruction (1900-1924) International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8 (4), 275-297

Pavlenko, Aneta (2005). ‘Ask Each Pupil About Her Methods of Cleaning’: Ideologies of Language and Gender in Americanisation Instruction (1900-1924) International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8 (4), 275-297

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

I recently found a good example in the Waseda University (Tokyo) School of Social Sciences (of all places). All the signs in the toilet cubicles were written in both English and Japanese except the following, which was in English only:

“Please dispose of used toilet paper in the toilet bowl and flush it properly. And be reminded the separately attached container is only for use of pad disposal. Thank You.”

Then of course there are all the sociocultural aspects of “toiletology” to navigate, such as how to tear non-serrated toilet paper in a straight line (that took me a couple of years to figure out) and how to leave the toilet politely for the next user by folding the edge of the toilet paper into a triangle. With all the recent advances in toilet technology in Japan, just figuring out how to flush the toilet can be an ordeal. In some recent designs the flush is a nicely hidden button on the top edge of a panel on the side wall. In a restaurant near my home with this type of toilet there is now a paper sign in Japanese posted on the wall explaining how to flush, so it’s obviously not just non-Japanese who are having difficulty fathoming this out.

The study of “Toiletology” can also go beyond the use of signs. For example, there seem to be different conventions regarding the use of toilet space for chatting. In the UK it’s quite common for two women chatting upon entering the main toilet room to continue their conversation after entering their own separate cubicles by shouting out to each other over the top of the doors. This is far less common in Japan. My Japanese students insist that it does happen but after almost 20 years in Japan I have yet to witness once.

An American graduate student of mine also pointed out that she often feels uncomfortable chatting in Japanese toilets because often there is no door separating the main toilet room from the outside corridor so anyone passing by outside can overhear the conversation and any other noises. Noises from inside the cubicles can of course be hidden by using the “oto-hime” (the sound princess), a device that plays the sound of flushing water.

Very interesting and important interpretation of toilte signage. As you have pointed out that selecting particular languages for these signage can be very offending to the self-esteem of people whose languages have been spotted which is so true. Looking it from CDA perspective, it also tell us the power inequalities in the multiculatural Australia? There are those who are the prodcuers of these text and there are those who only consume them without asking anything.

Who is excercising power in these toilete signage?. The one who has literally written these? or the people behind the scene? The mere selection of the languages reinforce the popular discourses around the speakers of these languages in Australia and elswhere.

There must be ethical codes and procedures in place for putting up these signages because languges are such important aspect of one’s identity, image, values etc. The world has to realise the importance of languge use in Public.

In late 2003, a sign above the urinal(s) in the men’s toilet serving the immigration office in Yokkaichi, Mie-ken, Japan said, “Don’t discard chewing gum here” in English and Portuguese but not in Japanese (nor Chinese nor Korean).

In October 2009 the sign was no longer there. While serving (us) client / petitioners, the immigration officers no longer smoked, nor did anyone else.

Thank you, Xiaoxiao! That’s why I’m blogging 🙂

An afterthought about my previous comment: I wonder if it’s possible to spread or broadcast the messages of such blogs to the relevant people or government agencies. The frequent exposure to such messages will at least make them think about what they can do to improve the current public signage. Or they do have access to such messages, but they simply ignore?

Wow, so much can be read and wrritten out of toilet signage. It’s something totally new and enlightening! We can surely learn a lot from this blog. But how about those people who work on such public signage? If they could keep reading Ingrid’s blogs, they would make this world a place to live in for all of us, despite our color, race or gender.

As an Asian, I do feel uncomfortable using public sit-on toilets, taking hygiene into consideration. As Ingrid said, providing flexible choices of toilets in Australia with a large influx of immigrants and visitors would be a concrete step towards a more democratic and inclusive society.

PS: “Toiletlogy” could be a new area of inquiry in sociolinguistics soon.

Really appreciate for your sharing this great idea. It’s amazing that such a small place (toilet) can bring this kind of discussion…. I really love the term ‘toiletology’…. ^^

I also usually enjoy reading something scribbled (saying something very directly ^^) or advertisement or promotion (particularly the items or the titles) on the toilet door or wall … while I’m sitting on the toiletbowl(^^)….

Admiring your photo collection, now toilets have a new level of sociolinguistic significance to me. Well said about the flexibility of choice – it never occured to me, but it makes perfect sense…