Recently, I asked my German-speaking, Berlin-based daughter Nanna whether she was able to understand our English-speaking neighbour when he talks with his daughter, Nanna’s best friend. Nanna laughed and obviously thought my question to be funny and replied: “Mami, ich kann doch kein Berlinisch!” which could be roughly translated as “Mummy, you know I don’t speak Berlinish!”. Of course, I also had to laugh and asked myself what it might mean that a German five-year old, with an otherwise fairly good understanding of semantic categories, confuses the language English with a German dialect.

We, Nanna, our second daughter, my partner and I, used to live in Frankfurt, Germany, spend some time in Australia, and have now been living in Berlin for more than a year. Since our arrival, I have been astonished by the amount of English that is spoken on the streets of Berlin. And, surprisingly, it has turned out that Berlin seems to be so popular that many of our friends from other places (e.g., Australia, France, UK, US, Denmark) have either moved to Berlin or visit us regularly. One effect of this is that, most of the time when we see our friends, we communicate in English. Adding to the fact that neighbourhoods like Friedrichshain, Kreuzberg, Mitte or Neukölln, are full of tourists and cafés in which people hang out and speak English, it becomes less surprising that Nanna thinks that English is what the people of Berlin speak.

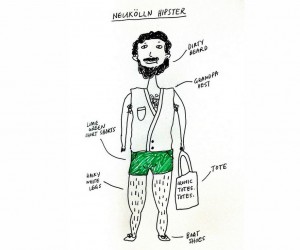

The question arises whether English actually has become a local language of Berlin. Considering established frameworks of sociolinguistics, we would probably say ‘no’. Think of Kachru’s circle model, where Germany is seen as being part of the “expanding circle”, with English as a ‘foreign’ language. Yet, many speakers in Berlin are not actually ‘foreign’ speakers: they may be ‘foreign’ to Germany from a legal point of view but live here and English is not ‘foreign’ to them. Plus, they are neither ‘foreign’ to a particular sort of culture that is very prominent in the neighbourhoods mentioned, often related to music, art, design and regularly criticised as producing gentrification and Hipsters, now a Berlin cliché. As these environments are often made up of a mix of people from many different countries, including migrants from EU states with high numbers of youth unemployment, English has been established as the lingua franca. And, obviously, this very lifestyle is neither ‘foreign’ to the Germans who participate, who use English on a daily basis and for whom, consequently, English is part of their local experience.

One consideration that may evolve from these observations is related to the analytical and social relevance of the terms ‘global’ and ‘local’. While English is usually regarded to be a ‘global’ language that may become localised in different contexts, these notions may be problematised as vague and as making invisible power inequalities. What do we mean if we say that English is a ‘global’ language? Does the focus on the territorial spread of English make invisible the discourses – based on neoliberal capitalism, colonialism, cultural industries, consumerism – that are responsible for its spread? Does the focus on territorial concepts like ‘global’ and ‘local’ thus enforce the hegemonic, neutralised status of English? And, for the generation of Nanna, do distinctions of global vs. local rather become historical markers, comparable to the history of the potato, now a signifier of Germanness, despite its South American origins?

Scholars have tried to grasp these issues. The notion of glocal is certainly amongst the more prominent ones, attempting to blend both terms together, semantically as well as linguistically. And it is not new to argue that “the dualities of the global and the local, the national and the international, us and them, have dissolved and merged together in new forms that require conceptual and empirical analysis” (Beck and Sznaider 2006:3). In the context of sociolinguistics, the term supervernacular focuses on the fact that a discursive construction like ‘the language English’ is always necessarily localised and is thus, necessarily, realised as a vernacular of that powerful discourse of ‘English’. Accordingly, the ‘English’ spoken in Berlin is a phenomenon that appropriates a discourse of power – speakers demonstrate access to a very powerful linguistic resource – and establishes a vernacular that is local and transnational at the same time.

Using English in Berlin can, of course, mean very different things. Yet, in the context of the specific neighbourhoods mentioned, ‘English’ often signifies access to transnational Communities of Practice that are based in the production of particular forms of lifestyle and in the performance of particular jobs, so, basically, it is an index of a transnational type of class.

At the same time, categories of space seem to remain relevant, as in the example of the term Berlinish, which is a form of localization. All in all it seems that concentrating on territorial distinctions (global – local), without discussing their intersections with economic, cultural and historical discourses, may hide the fact that any face-to-face language use is necessarily local; and it may also hide the fact that any language use is to be analysed as an instance of multivocality, where power differentials are of higher relevance for language choice than geographical trajectories.

Do we reproduce power differentials if we constantly mark the geographical origin of a linguistic resource that has been rendered socially and economically salient – and, as an effect, has spread globally? In this context, we may also ask: Whose ‘English’ is called English and to whose ‘English’ is a localised name attached (which then is typically seen as requiring subtitles in ‘English’ broadcasting)?

In all its temporality and contingency, and although formal education will most certainly put an end to it: Is Nanna’s concept of Berlinish a revolutionary appropriation of ‘English’?

![]() Beck, Ulrich and Natan Sznaider (2006). Unpacking Cosmopolitanism for the Social Sciences: A Research Agenda The British Journal of Sociology, 1-23 DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00091.x

Beck, Ulrich and Natan Sznaider (2006). Unpacking Cosmopolitanism for the Social Sciences: A Research Agenda The British Journal of Sociology, 1-23 DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00091.x

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Hey Christof,

Vielen Dank fuer deinen tollen Blogentry. War sehr interessant 🙂 You pose thought provoking and important questions. My own research interests go directly to many of the questions you pose. I will say that I definitely lean toward clear “ja” answers to both of these questions:

I’d totally agree that English is a local dialect in Berlin. Some companies even advertise their jobs explicitly to an english-speaking audience (here one example: http://madvertise.com/en/company/career/ ) although they are germanybased and germanrun. some of my friends live in berlin for many years now and don’t speak a single word of german (except of “Guten Tag” and “Bratwurst”, of course).

Hey Christof,

thanks for your comment, I have followed some of your comments in the past and always really could relate to them and it is great to be in touch! 🙂

it is true what you say about the one way street, which is really a dilemma. It still seems really awkward to me if people are really, truly monolingual, because this is not an option one has in my daily context and I really think that monolingualism is very limiting. On the other hand, although I am always trying to be really critical, I have to say that English also gives me a lot of opportunities and there are many friends who wouldn’t be friends (including many non-native English speakers) if it wasn’t for English. In this way, English is limiting and opening at the same time…

I recently watched this movie on Esperanto with my students http://esperantodocumentary.com/en/about-the-film and in this context, although it all seems very utopian, I really liked it for its idealism. Maybe we should try to make English a bit more like Esperanto in emphasising its democratic and inclusive functions? I really don’t know…

Britta,

Vielen Dank fuer deinen tollen Blogentry. War sehr interessant 🙂 You pose thought provoking and important questions. My own research interests go directly to many of the questions you pose. I will say that I definitely lean toward clear “ja” answers to both of these questions:

Does the focus on the territorial spread of English make invisible the discourses – based on neoliberal capitalism, colonialism, cultural industries, consumerism – that are responsible for its spread? Does the focus on territorial concepts like ‘global’ and ‘local’ thus enforce the hegemonic, neutralised status of English?

As an American who’s pretty much spent his whole life swimming against the linguistic stream — trying valiantly to acquire fluency in German while swimming against the tide of English globally, in the U.S., and, even in Germany itself — I can say that I dream of having easy/multiple and everyday opportunities to be multilingual in German and English in the U.S., as well as seeing such opportunities for my two daughters, whom we are raising as German-English bilinguals, even though German is a second language for me, and my wife is English monolingual. However, I know this is just a fantasy, and it will never happen. English is indeed virtually everywhere, at least in “global” urban centers, and especially in “cosmopolitan” places such as Berlin, Germany, but sadly it’s very much a one-way street/one-way flow, at least in relation to the U.S. & Germany.