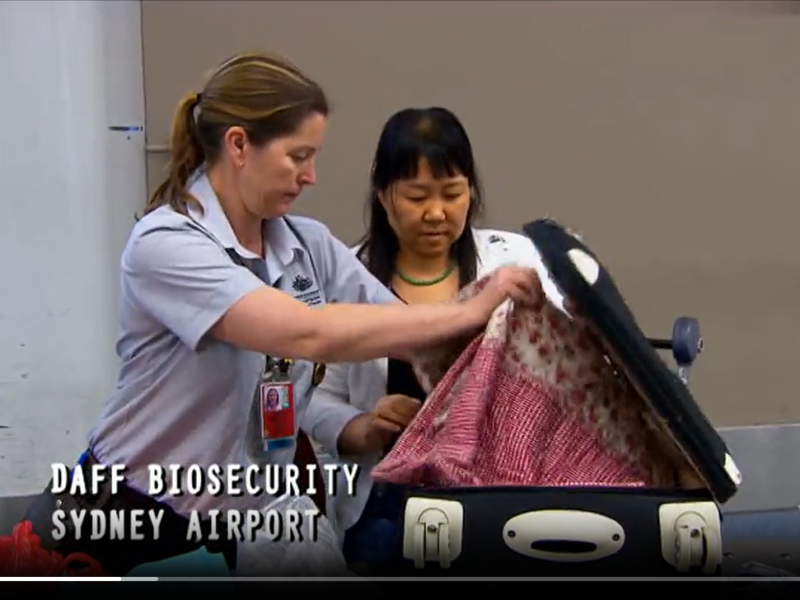

Screenshot of passenger being placed under suspicion on “Border Security”

Anyone who has ever travelled to or from Australia will agree that the last thing you want after getting off a long-haul flight is any further barriers between you and the outside world, a shower, and a bed. However, given the ever-increasing securitization of borders across the global north, international travellers must first succeed in convincing border officials that they do not pose any type of threat to the nation.

This may be much easier for some people than others. In a recent study, we examined the various aspects of individuals’ language, identity and behaviour that are made salient by border officials in their work, when deciding whether particular people are suspicious or can be trusted. To explore this question, we collected and analysed 108 encounters between border officials and travellers arriving at Australian airports, filmed, produced and broadcast as part of the long-running, popular television series, Border Security: Australia’s Front Line.

In our new article, we show how in these encounters, border officials carry out evaluations of travellers’ credibility, much like those used in other migration processes, such as the assessment of asylum claims. We find that different individuals are unequally positioned to construct a trustworthy identity based on the way they speak, their social capital, their (perceived or actual) nationality or ethnic origin, their knowledge, and material factors, like the clothes they wear, the money they have, or the other items in their possession.

Officer: (to camera) “This gentleman has arrived on an Italian passport. Speaking to him our officers realized that he’s not a native Italian speaker. The question is now what is his nationality.”

Screenshot of passenger being placed under suspicion on “Border Security”

These factors are made salient in ways that are unreliable and inconsistent, and we critically examine and denaturalize the problematic assumptions underlying them. For example, in the encounter above, Italian citizenship, a political/legal status, is imagined to involve specific social and linguistic experiences and practices, being born and raised in an Italian speaking context, to the exclusion of others, such as migration and naturalization.

In each case, we also compare how border officials are in a stronger position to mobilize the same categories of resources to construct identities for themselves that are trustworthy and credible.

This, we argue, is due largely to the privileged position they have on two different levels, both in terms of how they can control the discourse within their interactions with individual travellers, but also at the level of the television show, in how discourse about these interactions is produced and disseminated.

At the level of the encounters, officials obviously have a very specific role to play: they are the ones who decide who to stop, how to question them, what technologies to use, and, ultimately, how they interpret what they see and hear.

Officer: When we commenced our interview, I specifically stated to you that pursuant to Section 234 of the Migration Act, you’re required to provide me with truthful information. Can you demonstrate to me conclusively that you did work on that farm? I’ll give you this opportunity again, Declan, I’m a pretty fair sort of a guy.

Screenshot of passenger being placed under suspicion on “Border Security”

Not only this, but officers wield power over travellers in terms of the outcomes of these encounters: they may issue fines or warnings, cancel people’s visas and have them deported, or refer them for police investigation. This power undoubtedly influences the way travellers interact with them, and their perceived and actual levels of discursive agency.

However, the inequality does not end there: the television show itself produces discourse about traveller credibility, both in relation to the individuals who appear in the various encounters, but also in terms of the general messages that come from the combination of such interactions. At this level, we identify a range of discursive strategies, including giving the floor to officials to explain to camera the reasons for their suspicions and final decisions, and the use of an omniscient narrator who plays a similar role.

Such is the level of discursive inequality that, for instance, two friends returning to Australia after an overseas trip and going through passport control separately – as required for non-family groups – can become a “hidden” fact to be uncovered and construed as suspicious.

Narrator: Officers have just discovered what seems like a strange coincidence. A passenger at another bench has virtually IDENTICAL travel movements. […] Officers now suspect that these two passengers may in fact know each other.

Screenshot of passenger being placed under suspicion on “Border Security”

This adds another layer of credibility to officials’ border work: along with the show’s narrator, they have a chance to explicitly describe their reasoning processes and the accommodations they offer travellers, to perform procedural fairness for the viewing public.

At the same time, it also provides an additional opportunity to teach the viewing audience to suspect certain types of people and problematize certain attributes or behaviour. We learn, for instance, that people who hold an Italian passport should speak Italian natively, and that not doing so is cause for suspicion.

We learn that travellers from particular countries or ethnicities should be treated with a higher level of suspicion and that their behaviour or explanations require closer scrutiny. The two friends mentioned above weren’t just travelling together – they were travelling to countries in South-East Asia and are themselves of Asian ethnicity. These facts contributed to framing their trip together and their behaviour in the airport as suspicious, where these may otherwise appear completely innocuous.

This is apparent in the individual encounters themselves and how they are narrated, but this is also the case cumulatively, across the television show as a whole: non-white, non-Australian people and those who don’t speak English as a first language are overrepresented as travellers in the show, and can be contrasted with border officials who are predominately white, and “Australian-accented” English speakers (as we discuss in another article).

Screenshot of passenger being placed under suspicion on “Border Security”

Detection of wrongdoing is also overrepresented: in 61 percent of the encounters in our collection, there was a “guilty” outcome: people are detected, fined, have food or goods confiscated, or are arrested or deported. We can imagine that this is vastly disproportionate with the percentage of “wrongdoers” detected in reality. The combined effect of this is that viewers are taught that there is a high level of wrongdoing, meriting a high level of suspicion, and that this needs to be directed primarily at society’s linguistic and racial “others”.

These findings have implications beyond the television show itself: such discourses of suspicion have the potential to encourage viewers to take on personal responsibility for everyday bordering in their own social contexts. They also help to reinforce and garner trust in border policy, procedures and practices, even as it has moved towards criminalizing asylum seekers and other migrants and adopting a “culture of suspicion”.

References

Piller, I., Securing the border of English and Whiteness. Language on the Move, 8 November 2021, https://languageonthemove.com/securing-the-borders-of-english-and-whiteness/

Piller, I., Torsh, H., & Smith-Khan, L. Securing the borders of English and Whiteness. Ethnicities. 2023; 23:5, 706-725. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211052610

Smith-Khan, L., Five language myths about refugee credibility. Language on the Move, 6 May 2020, https://languageonthemove.com/five-language-myths-about-refugee-credibility/

Smith-Khan, L., Piller, I., Torsh, H. Trust at the border: identifying risk and assessing credibility on reality television. Journal of Law and Society. 2024; 51:4 513–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12505

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Join the discussion One Comment